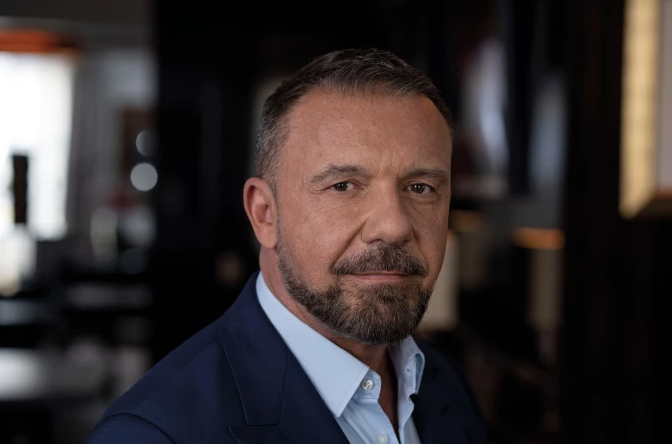

The grandson of Pablo Picasso, Olivier Widmaier Picasso has released an expansive documentary exploring the life and posthumous legal legacy of his grandfather, premiering on ARTE on the 50th anniversary of his death in April 2023. He talks Sotheby’s through the documentary’s making and how he views Picasso’s legacy today.

Olivier Widmaier Picasso, the grandson of Pablo Picasso and Marie-Therese Walter, is a lawyer, author and co-producer of a comprehensive new biography of his grandfather, ‘Picasso, The Legacy’ (aka ‘Picasso, L’inventaire D’Une Vie’ ), co-produced with ARTE France, Welcome, RMN-Grand Palais and Gedeon Productions, and supported by Sotheby’s.

The documentary is an epic overview of the artist’s life, reflecting on his artistic evolution from birth to death and the friends, rivals, lovers and global events that shaped that journey. It also adds a dimension hitherto unexplored in film by a member of the Picasso family, namely the incredibly complex legal narrative that unfolded following the artist’s death in 1973. Alongside the retelling of Picasso’s creative life, the narrative incorporates a phalanx of lawyers and estate executors, explaining their part in unraveling the tangled thicket of Picasso’s archives and liabilities, from an inventory of several tens of thousands of works.

This fascinating documentary recounts this epic story, which lasted seven years and led to the creation of the National Picasso Museum in Paris, using works of art in lieu of inheritance taxes. Exclusive testimonials, archival documents, family photographs and deliciously rare footage reveals Picasso’s inner and public life with unprecedented insights and perspectives.

In the documentary, the sorting, classifying and apportioning of the artist’s extensive archive makes for a truly compelling tale. And thanks to Olivier’s energetic pursuit of a fully-rounded portrait, close friends and family members are interviewed for the film, including Françoise Gilot, Olivier’s late mother Maya Widmaier Picasso, Claude Ruiz-Picasso, and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso alongside exclusive testimonials, archival documents, family photographs and films

Ahead of the film’s premiere on ARTE France, Olivier called us up from Miami to reflect on the making of the film – indeed why it needed to be made – and what he makes of the enduring legacy of his grandfather, still indubitably, the greatest Western artist of the 20th century.

You’ve been involved with Picasso documentaries and books in the past – what motivated you to embark on this ambitious documentary?

When I decided in 2014 to make this film it was to be the first time a full documentary would be made about my grandfather and his life. There had been others of course, but they were old, from 1997 or 1970. So, it was a big job. And I wanted it to be sufficiently interesting for the people who don’t know about Picasso, as well as being interesting for the people who have a lot of knowledge about him and his works. So we made in a way that would get and retain the attention. This is why the director Hugues Nancy started the film with the flashback [to reports of Picasso’s death] it was like a flashback on his life, a connection between the artist and the man.

The film is structured in a way that we experience parallel narratives – Picasso’s artistic and personal journey, interspersed with the posthumous complex legal activity as the estate is categorised for tax, legacy and heritage purposes. Why did you choose to present these narrative strands in parallel?

Exactly, yes, I felt it was necessary to explain why and how Pablo Picasso kept so many artworks. It was interesting to show the process of the estate with the French government, because at the time of his passing, his heirs, his children, were not about to create a ‘dation’ – a list of artworks to be given in lieu of inheritance taxes – but to offer the French state the first choice. And I think they thought that was the best way to do it. It was not unintentional that Pablo Picasso had kept so many artworks from every period, you know he was probably trying to create the perfect museum, maybe it was a way of him saying, hey, this is what I leave to humanity.

“Picasso himself said, there is enough for everybody. But he didn’t want to make a will, he didn’t want to discuss his death, he was just trying to survive as much as he could”

So, you worked on this film with the director Hugues Nancy, and spoke to members of the extended Picasso family, as well as a number of experts, curators, lawyers and friends. How did you begin to corral a structure and narrative from this wealth of resources?

The book I wrote earlier [Picasso: The Real Family Story (2004)]helped a lot with the structure – clarifying the subject, the period, the people, the family, the women. But I wanted the director Hugues Nancy, who has an artistic eye, to be completely free to criticise my work and to create a new relation between us. So, let’s say I gave him a structure and he finalised the details. Like when you have a building, you have the structure of the building and then you can decide about the decoration!

He did the interviews, because I knew most of the people we featured and I didn’t want to use the intimacy I have with my mother, or with Claude Picasso, with Bernard. So, I wanted him to feel free about the style. We prepared the questions together, but he did the interviews, except for Françoise Gilot, which I did. I didn’t have the same closeness with her that I did with other members of my family, so it was easy to talk to her, to ask questions and she was very funny, she was at that time, around 94, and now she’s 102! She’s still a vivid person, I was astonished by the woman and so yes, I could understand what happened in 1963, when she told Picasso, ‘Goodbye!’

She does come across a very lively character! And with your own history in law and business, it was also fascinating seeing you interview numerous legal and business people who were involved with the estate and the aftermath of his death. Especially as they all seem to have been so profoundly moved by their memories of Picasso and clearly, felt a connection with his art.

All those lawyers, experts, auctioneers, notaries – they are normally at court discussing serious subjects and then suddenly they have colours in front of them! It was very funny to have a serious lawyer, talking about how crazy it was to find a letter on the floor written to Picasso from Apollinaire! This was really interesting to have those guys for such a very different approach to their usual job.

It was such a dense complex legal affair…

Yes! When I was a child, I didn’t understand this complicated situation, it was complicated for even the adult family members. But, after studying law, I understood that there was a solution for everything. For example, when Pablo wanted to get divorced from his first wife Olga to marry my grandmother, it was illegal to divorce in Franco’s Spain. And Olga, his wife, didn’t want to get divorced! She wanted to be Lady Picasso! His grandson, my cousin Bernard, explains very well [in the film] that the moment people knew that she was going to be divorced, it was like – goodbye! She was banned from the Parisian society she was part of. And it was interesting to see for her it seemed more important for her to appear to be still married, than to get half of his fortune! Today, it’s usually the contrary!

So, it was interesting to show that and then the matter of the children’s rights. In fact, in France, the Napoleonic code was established to protect the family. You could have as many children as you want outside of marriage, but those children would have no rights. So, in the past, the children were paying the consequences for the actions of their parents. Today, it is the contrary, everybody is equal, and parents must be very careful if they fool around! So, this was important to me, and I think that studying law helped me to dig into documents, into certification, into attestation, the laws themselves, to understand this history of my grandfather.

“When I was a child, I didn’t understand this complicated situation, it was complicated for even the adult family members. But, after studying law, I understood that there was a solution for everything”

As well as exploring the tangled legal ramifications of the legacy, you have spent years navigating the dense networks of family and relationships. What is it like being a part of this complex web?

On one side, I am very lucky because of the name, the fame, the inheritance. On the other side, we have an obligation to be very strict with the truth and even today, where you have cancel-culture, interrogation of this or that celebrity, it is even more important to be very precise.

So was this a concern of yours, when you began work on the film, to address the negative views some have of Picasso’s attitude to the women in his life?

No, no, when we started with this film it was before the Me-Too movement and we were not in this situation. But, I was respecting the situation of Olga, the married woman, Therese, the young muse and lover, and Dora Maar, the sophisticated intellectual woman and then Francoise Gilot who knew exactly what Picasso was! And then there was the situation of Jacqueline, a very strong woman, who was there in the last years of his life. So, I think it’s easy to mention the guy who had had relationships with several women – he was not like a predator! They were there, they were necessary for his creation. You must consider, all those love stories were over 70 years, not just a few months or a few years.

And then you had the Second World War. And during the war, nothing moves, everything is frozen and the situation with Pablo, the women, the children – it was frozen.

So, you have the right to question people, but only if you are educated. Otherwise – well, I could turn around and say, well, Elvis Presley was a womaniser! OK, but before I say that I need to understand what the situation was in the 1950s or 1960s.

It’s hard to judge accurately, and retrospectively. Human lives are messy. Especially artists’ lives. But the film explains eloquently how the emotional attachments impact on his work as he moves from Olga to Marie Therese, to Dora Maar.

Because I am old enough – I remember meeting Marie Therese, my grandmother, and she had character! She was not someone sleepy! She spoke of the past with nostalgia and enthusiasm, I don’t remember her talking of any perversity or pain – she had a time with an exceptional person, and he was not like the boy next door – and it gave her a kind of immortality in museums, galleries, and private homes – and he gave her a lot of artworks. She was given the most artworks of anyone in the family before he died and she knew she was young, that she grew up with him and she also knew when that story was over, and it was hard for her to find another man. No one compared to Pablo Picasso.

And I think that to me, she was not a slave – she had to be discreet at the beginning as he was a married man – but she never suffered in the situation. So, it’s important to get educated about this, to make a judgement. Of course, if you consider a guy of 46 years old having an affair with a woman of 17 today, then that’s … quite difficult to accept. But at that time, it was more common. But – by the way, I am in Miami and when I go to restaurants, I see a lot of old rich men with very young women in love – with their Chanel bags! So, it’s not so unusual to have a large difference in age between people. It’s a choice.

Yes, this is true, but if a man is exploiting a younger woman, then that is an unacceptable situation – but yes, in the film, we see his relationships are presented as collaborations with very defined and distinct women.

Yes, you’re right – it’s interesting how those women (in Picasso’s life) were different. It’s very interesting how much he was curious of the humanity in people, because those women were all different, yes, but they were all essential to his creativity. Because if you suppress Olga, you don’t have the neo-classicism of the 1920s, if you remove Marie-Therese, there is no Surrealism, if you remove Francoise Gilot, there is no ceramics or maybe, the dialogue with Matisse – so, everyone was different. He was very curious and could not be satisfied with a boring situation. I think it’s important to be educated – even me, I am not an art historian, I am not a journalist, but I try my best to be balanced and forget my situation. But then my situation has given me a lot of access to information that no one else could have access to, like some of my memories, from when I was a teenager during these years.

When you were making the film, all this information you had – did you discover anything that you hadn’t known before?

I think that before my exploration of Picasso, I didn’t have a real sense of his humanity, his connection to people or history. He was very curious about the past, the present and always anticipating the future. So, it was important for me to show the humanity of the guy. It’s complicated when you speak about fame, about sex, about relationships, its complicated to be human. So, this gave me a reason to talk to people like my uncle, my mother, or to legal people, his lawyers in the 1960s, to understand – what was his daily life? Because the life of Picasso for me was mainly found in museums and in the memories of my mother, but otherwise nothing. So, I discovered the humanity. And whatever happened, if there was something important, he always had to go back to his studio to face his creations, by himself. His energy – he was 60, 70, 80, 90 – and he was still driven by so much energy, it was supernatural! So, I wanted people to understand that as well as the enormous number of artworks, so many techniques, I also wanted people to understand the man himself – and I think we explored that to the maximum.

“I wanted people to understand – as well as the enormous number of artworks, so many techniques – the man himself”

What do you have happening next? Are there more Picasso stories?

I think I’ve done the maximum I can do, despite not being an art student or journalist or historian, but I think maybe it might be next interesting to explore the collaborations of Pablo Picasso. Because critics and writers always want to make a link between artists and Picasso! Yet a lot of artists are also tired of hearing about that! But then, even with the most eminent of artists, when you ask, they tell you something about him. For instance, Jeff Koons told me that he remembers the day Picasso died very well. He was in Pennsylvania, in the school of fine art and he told me that the day after his death, he told all his friends, I want to be like Picasso. And then he became Jeff Koons!